Who Lives in Yerevan?

The strongest impression of my first day in Yerevan was the fact that there seemed to be only one archetype of appearance and one prevailing language in the city streets. Armenia is a mono-national country: according to official statistics, more than 97% of its population is purebred Armenians, and the rare tourists are noticeable immediately. There is no animosity towards foreigners in Yerevan; however, people do keep their distance. It soon became clear to me that penetrating into the inner life of the city would only be possible with the help of Armenian friends.

The homogeneity of the urban area was so unusual that I immediately wanted to ask: “Besides Armenians, who else lives in Armenia?” It turned out that there are numerically small communities of Kurds, Yazidis, Assyrians, Greeks, and Molokans, which, however, are closed to outsiders. None of my Armenian acquaintances had friendly or professional ties with the representatives of these ethnic minorities.

The street crowds in Yerevan became more diverse in my eyes as soon as I learned to distinguish the locals from Armenia’s main tourists – Iranians. Armenians semi-contemptuously call them “Persians” and claim that they “come to Armenia to blow off steam by getting wasted and picking up girls.” Every evening groups of “Persians” would gather at the Republic Square to marvel at the singing fountains. Most of them were quite approachable, and it just so happened that I managed to draw dozens of Iranian men and women during my first days in Yerevan.

“Turks will Be Turks”

As opposed to Russia, where people are alienated from each other, mutual support and mutual control are ingrained in Armenian society. The idea that the Armenian state is one united family is supported at the state level, and it makes the internal critique of authorities rather problematic. Participants of Electric Yerevan, a round-the-clock demonstration in Yerevan against the hike in power prices, told me how the police tried to appeal to their conscience by saying, “We are all brothers and sisters after all!”

Musicians on Northern Avenue

The subject of Armenian Genocide comes up constantly. On the very first poster at the airport, a Turk is compared to Hitler. Every evening street musicians on Northern Avenue would play songs about the Armenian resistance against Turkish assaults, and diaspora Armenians visiting Yerevan in summer would instantaneously surround them and sing along eagerly. Many demonstrators during Electric Yerevan also sang songs about Genocide in protest.

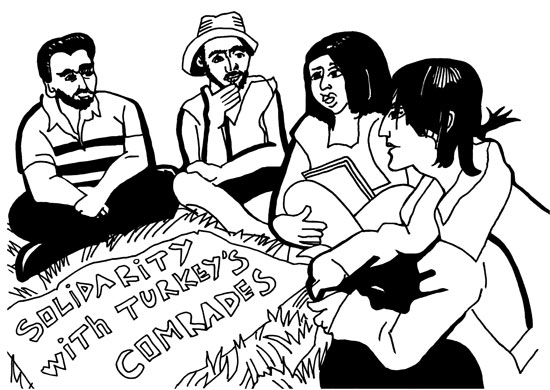

There is a saying in Armenia: “Turks will be Turks.” As in “bad.” The progressive youth of Yerevan, however, follows the social processes in Turkey with interest and sympathizes with the country’s leftist movement. While in Yerevan, I attended a meeting with social activists who discussed how to operatively translate and distribute articles about the anti-government actions in Turkey which started after the terrorist attacks in Suruç. State media hardly ever cover stories about neighboring Turkey, Iran, or Azerbaijan.

In the City Center

A woman selling sunflower seeds near the Opera Square

If you wandered about downtown Yerevan without looking into inner courtyards, you’d notice that with its yearning for grandeur the city can quite resemble Moscow.

During the first few days, I couldn’t figure out where to buy cheap local fruits and vegetables: the nearest market is only reachable by bus, street trading is non-existent, while prices in chain stores are almost as high as in Moscow. Then I was told I should look for private traders’ shops (kiosks and outhouses) in residential courtyards.

You can get tasty, cheap meals in unpretentious cafes opened by Syrian refugees; local Armenians, meanwhile, run restaurants. In Yerevan, much like in Moscow, the culture of “second-hands” is not very developed; expensive brand stores, on the other hand, are plentiful. In the evenings the downtown is filled with people wearing fashionable clothes, as if they were on a runway – close-cropped black-clad men and long-haired women in slimfit dresses with low-cut necklines.

Walking among the crowds, one can also encounter women involved in prostitution. Once I even witnessed a scandal at the Republic Square when a man remarked on a sex-worker’s “disgraceful occupation” and she replied in the fashion of “my body is my own business.”

When I was trying to draw the scene, another sex-worker suddenly grabbed my arm and started yelling so loudly that dozens of pimps immediately ran over to us. Luckily, the heroine protected my sketchbook from reprisal and even agreed to pose for a portrait.

The sex-worker from Republic Square

Public Space

There are lots of fun and interesting things to see in Yerevan’s inner courtyards. Tiny private barbershops, for instance, where you can get your hair cut, play backgammon, and discuss politics. Walking in Yerevan, we once ran into one such salon, and my Armenian friends asked them to let me draw there.

“When I was little I was taught that Chapayev was our main national hero.”

It turned out that famous Armenian artist Simon Galstyan’s son was one of the regulars of this barbershop; he started to criticize the imposition of the Russian language and culture during the Soviet era, while in his arguments against colonialism he kept quoting Tolstoy and other Russian classics. To date, the majority of Yerevan residents speak Russian, and full sentences in Russian occasionally pop up during conversations.

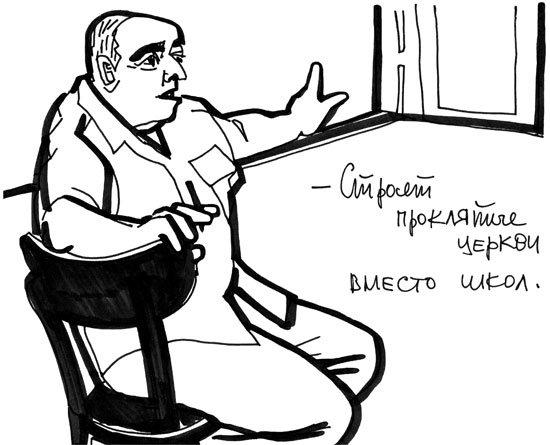

We also touched upon the subject of construction in Yerevan.

“They’re building damned churches instead of schools!”

I heard the following opinion on multiple occasions in Yerevan’s artistic and activist circles – Armenians think that any and all land lot should have an owner, be built up and used for profit. The city’s public space can easily become someone’s property. For example, in 2002 millionaire Gerard Cafesjian bought the Cascade complex, one of the Armenian capital’s main symbols. Some of Yerevan’s key parks have also passed into private ownership.

Ordinary citizens occupy urban space by the very few means available to them: the small plots of land in front of residential buildings turn into private gardens of first-floor tenants, additional rooms supported by columns get attached to the facade of tower blocks.

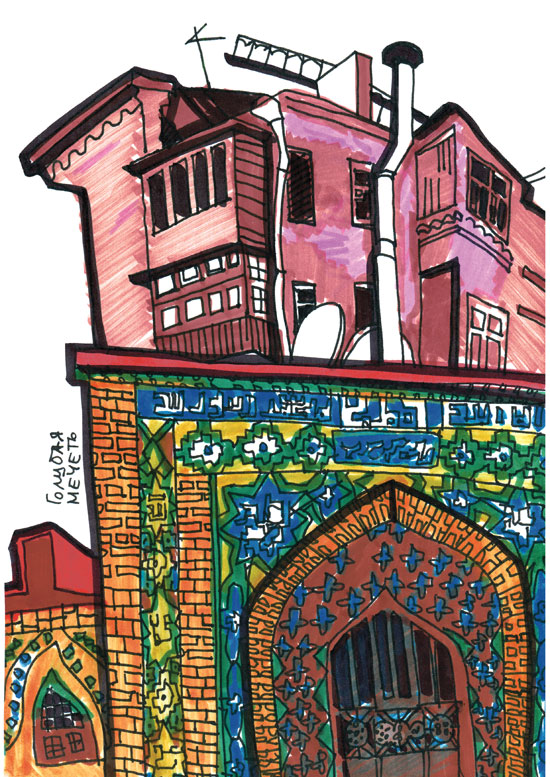

The Blue Mosque and Grandpa Lenin

Yerevan is perhaps one of the most reconstructed cities.

The only keepsake from the period of the Erivan Khanate is the Blue Mosque, which is closely surrounded by apartment blocks, as well as part of the Kond district. The famous Ararat Wine Factory currently occupies the place where The Erivan Fortress and the Palace of the Sardars once stood.

The Blue Mosque

Several Iranian mosques and Armenian churches were destroyed in the Soviet times; after the fall of the USSR, in turn, a number of Soviet buildings were demolished, including the modernist Youth Palace of Yerevan, and the hotel “Sevan”; only the citizens’ protests saved the avant-garde summer hall of Moscow Cinema, which authorities were planning to replace with a church.

During reconstruction, numerous Soviet symbols were also dismantled. The Lenin Square was renamed to Republic Square, while the statue of the Soviet leader was dropped off the pedestal and beheaded. My artist friends told me that the headless Lenin currently lies in the courtyard of the National Art Gallery. One cannot enter the yard without a special permit; however, the statue can be seen from a gallery window. So I bought a ticket and found the right window: headless Lenin was absurdly lying in an idle fountain. One of the guards got seriously worried about my drawing: “Don’t show this painting to anyone! Don’t tell anyone he’s lying here!” She, however, was unable to explain why it was such a dangerous secret.

Kond

Back in the early 2000s, an entire street in downtown Yerevan was demolished to be replaced with the “elite” Northern Avenue, while many of the forcibly evicted people instead of new apartments only received minimal monetary compensation. The demolition of Kond – Yerevan’s oldest district – is also being discussed by authorities.

Kond is reminiscent of an anthill: pre-revolutionary houses located on a big, rocky hill; narrow, loopy streets, many of which come to a dead end. These stone houses were once built by wealthy people. Today, however, Kond mostly looks like a slum. There is even a dilapidated, old Iranian mosque in the district which has been housing 5 families since the Soviet times.

“How can you live in this ‘antique’ house?”

“Antique” sounds like an insult in Armenian; it means “junk.”

Kond is believed to be cursed by many of its residents since in the past most of the houses used to belong to Muslims – Iranians, Azeris, “Turks” (the Azerbaijani Tatars). At the same time, they are strongly attached to their community; the neighbors know each other well, and most of them are quite closely related. This dovecote owner, for example, would like it if all of the Kond inhabitants moved to a new, big house.

“We’ll move into an apartment and will keep the doves on the roof.”

Activist Nara

Not every Kond resident, however, dreams of moving away. While in Yerevan, I had the chance to visit activist Nara who lives with her mother in a house built by her grandparents who’d managed to flee Turkey before the genocide massacres. Nara is very fond of the house and wants to renovate it one day.

Activist Nara and her mom

Nara told me that in Soviet times local authorities demanded that owners of private houses give up property documents, and most of Kond residents, including her grandmother, obeyed this order. Upon learning that after the construction of Northern Avenue the inhabitants of the demolished blocks were thrown into the street, Kond residents became seriously worried about their own fate.

Nara went door to door in the district, calling on her neighbors to come together in a fight for their rights. As a result, the residents would take chairs to the Government building and sit there for hours, demanding restoration of property documents. And they succeeded.

“I’m not married, nor do I have a son or a brother, so they couldn’t frame me with drugs or arms.”

In Armenian society, pressure on women activists is usually put through their male relatives. Kond’s protests mainly featured women, and one elderly man – a Karabakh war veteran, so police did not disperse them forcibly. They, however, would try to negotiate with the sole male protester, ignoring Nara – the protest’s female leader.

Abovyan Women’s Prison

Thanks to the support of the Prisoners’ Rehabilitation Center under Armenia’s Justice Ministry, I was able to hold several drawing lessons in Abovyan Women’s Prison. The Center provides prisoners with legal and psychological assistance; in Abovyan, which is the closest prison to Yerevan, they regularly organize ceramic painting, stained glass, and wood carving lessons.

Nastya and one of Nastya’s murals

During my master classes I met Nastya, Abovyan’s star-artist, who’s painted the walls of the prison with several monumental murals. Nastya studies Saryan’s and Avetisyan’s paintings and then pays homage to their art.

There are plenty of trees on the territory of the prison, while the low walls with barbed wire on them do not fully block the view of the mountains. The inmates wear their own clothes. I was told that that female prisoners do not have to wear prison uniforms – “They are after all women!” – and that the regime in women’s prisons is softer than in men’s. There are no all female juvenile correctional facilities in Armenia – courts usually impose suspended sentences on underage girls.

At lunchtime a motley crowd of women entered the dining room, carrying pans and cast-iron pots full of food cooked with their own hands; almost no one eats prison food. Unlike Russia, where the vast majority of female prisoners are abandoned by their families, in Armenia relatives take care of the inmates throughout their entire term.

Abovyan Inmates

Most are in for conventional crimes: fraud, drug and human trafficking. Armenian women lure girls into sex slavery in Turkey – it’s close and there is demand. Women who’ve been imprisoned are forever labeled: they have minimal chances of finding a normal job, having a personal life, or marrying off their daughters.

Being an Armenian Woman

I was once taken for an Armenian in Yerevan. I was sitting on the ground painting the above pictured carpet sellers when an elderly woman approached me and started to carefully pull down my skirt while lecturing me in Armenian. Realizing that I was from Russia, she lost all interest in my moral character – “Russian woman” in Armenia is equivalent to “slut.”

It’s interesting how much different social pressures experienced by Russian and Armenian women are. In Russia, being a virgin past 19-years-old is unseemly: women are expected to have sexual relations with random men and have a baby. Even if they do have to be single mothers. On the other hand, family honor is the main value in Armenia’s society. Many women who did not manage to get married are regarded as “old maids” and can comfortably speak about it in public. The “Red Apple” tradition is still practiced in a number of Armenian regions – on the morning after the wedding night the groom’s family sends red apples to the bride’s parents to recognize the bride’s virginity. Getting “knocked up” without being married is shameful. Getting divorced is shameful. And remaining childless is the greatest woe.

Once an Armenian friend of mine noticed a bakery and suggested we take a joint interview from the women baking lavash. We were cordially seated at the table and offered coffee; however, our conversation about social changes in Yerevan totally flopped. The women were asking my friend in Armenian how old my children were (for some reason they were sure of their existence), while trying simultaneously to marry her off to their sons.

“Are you married?”

The only question I was asked.

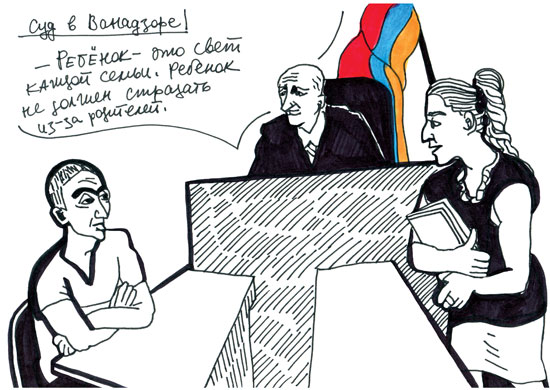

Domestic violence is as widespread in Armenia as it is in Russia. In 2010, seven women’s organizations united in the “Coalition to Stop Violence against Women” to lobby for the adoption of a law against domestic violence and provide assistance to victims. I attended Syuzanna’s hearing – domestic violence victim whom the Coalition accompanied to court having paid for her lawyer. The young woman used to be regularly beaten by her husband and mother-in-law, and when she decided to get a divorce, they took away her daughter. After the hearing, the judge preached to the former spouses to keep the family together and protect the honor of the Armenian society.

Vanadzor court: “The child is the light of every family. The child shouldn’t suffer because of the parents.”

Armenia also has a very particular kind of problem: the country ranks third after China and Azerbaijan in sex-selective abortions. Usually abortions are carried out when the family already has two daughters, and the sex of the future baby has also been determined to be female. A yet another unwanted daughter can be named “Bavakan” – i.e. “enough.”

The son is considered the descendant and future breadwinner of the family. The social status of a woman who gave birth to a son increases significantly. Traditionally, the son brings a wife to his parental home and inherits their property. The daughter moves in with her husband’s family, while an unmarried one caters to her brother’s family.

However, such patriarchal traditions gradually loosen in Armenia; Yerevan’s younger generation is very different from their parents. This is a portrait of social researcher, feminist Arevik with her mother, who is perplexed as to why her daughter is not in a rush to get married and have children.

Arevik’s mom: “I did my best to nurture her… Where did I go wrong?”

Meetings, interviews, and collaboration with independent women – these are my fondest memories from Yerevan. I believe that progressive reforms in Armenia will be primarily related to the increase in women’s activity.

Victoria Lomasko

Epress.am News from Armenia

Epress.am News from Armenia