The audience in Yerevan mainly enjoyed the Georgian films with the word “Karabakh” in the title but which were not about the conflict. The audience was rapt with attention and in the discussion following the screening recalled even the smallest details and scenes from the films. However, the audience never did admit its admiration of the films, preferring instead to focus on the “mistakes” of the filmmakers of Trip to Karabakh 1 and 2, “Armenians being shown as uneducated” and the “deliberate distortion of political realities.” In any case, this Karabakh was not about Armenians or Azeris. Simply a film is shot in Georgia and there is no pretending that no one other than them lives in their place of residence. But more on that below.

The screening was part of the STOP Festival organized by the Caucasus Center for Peace-Making Initiatives, which in 2010, was pressured for its attempt to organize a screening of Azerbaijani films in Armenia. On several occasions, human rights activist and festival organizer Center Georgy Vanyan was refused space to screen the films, as a result of which the screenings were held in people’s homes.

The first “trip” — “From Mimino till Today: Transformation of the South Caucasus” — was made by Conservative Party of Armenia leader Mikael Hayrapetyan and human rights activist Luiza Poghosyan.

Images of modern Georgian cinema broke out of Caucasians’ Soviet model of behavior. Hayrapetyan emphasized that Georgia, unlike Armenia, has taken a step forward in getting rid of the rules imposed on it by imperialism. He saw this in the film, which he didn’t consider from an artistic point of view, and he sees this when travelling to Georgia.

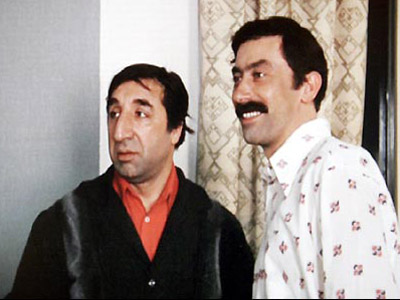

According to the politician, it is proposed Mimino and Rubik jan (characters in the 1977 Soviet film “Mimino”, pictured below) to get into a stupid fight about the best water and dolma in the world and to compete in a restaurant for the right to request a song from mediocre musicians. Hayrapetyan was sure that the discussion of pressing issues and the colonialists’ policies would turn careless South Caucasians into dissidents and lead them straight to the gulag.

Human rights defender Luiza Poghosyan, in turn, recalled Zurab Tsereteli’s “monument to Georgian-Russian-Armenian friendship” (pictured below) dedicated to the main characters of “Mimino” (played by Georgian actor Vakhtang Kikabidze, Russian actor Eugene Leonov, and Armenian actor Frunzik Mkrtchyan), which was banned in Moscow and was instead erected in 2011 in Tbilisi’s Armenian quarter. A “copy” of this work was erected in Dilijan, Armenia, the same year. In both sculptures, the Russian actor stands between the Armenian and Georgian actors.

In Tbilisi, the monument was erected in Avlabari (Havlabar). The opening ceremony was attended by Georgian President Mikail Saakashvili and his wife. There was also a protest of about 10 people shouting “Stop Zurab!” Poghosyan said she would join the protest against reinstating Soviet traditions of Armenian-Georgian mediated relations.

The Russian reporter in the film “Trip to Karabakh” regularly asks the Georgian guy who accidentally finds himself among Armenians also freed from Azerbaijani captivity, “Who are you? How did you get here? Do Georgians like Armenians?” He answers, “Leave me alone. What business is it of yours? We’ll deal with our issues ourselves!” Asked “Don’t you like Russians?”, Gio says, “I don’t like scoundrels.” But then they have sex.

Poghosyan also pointed out, “it seems the images of Armenians are cut out of cardboard.” Georgians’ contact with Armenians as such doesn’t occur, while Georgians’ contact with Azerbaijani soldiers is more human, despite the beatings on the first day of captivity. The Armenians call their new quiet comrade “brother” and drink toasts to their ancestors of the Christian Caucasus, but criticize his country for the civil war, for the fact that “Georgians are shooting at Georgians.” He seems free to do whatever he wants but in fact is under constant supervision. In the end, he takes the Russian reporter hostage, grabs two Azerbaijani prisoners of war and flees to save his friend. One of the Armenians says after him, “I told you he was a son of a bitch.”

During the discussion following the film, the comments began with the fact that the film was easy to watch, the characters were well developed (except from the Armenians, it seems). When audience members began to analyze the film from the view of the Georgian filmmakers’ sympathies to one side of the Karabakh conflict, they approached the minute issues that can be seen if only this aspect of the film is observed. For example, a secondary school teacher said that Armenians in Azerbaijani captivity had cigarettes, and there were no signs of beating on their faces, while Azerbaijani soldiers in Armenian captivity asked for something to eat and were severely beaten.

Along the same line, the filmmakers can be accused of having anti-Armenian sentiments: the Azerbaijani soldiers have access to drugs, they eat kebab (while Armenians eat canned food), their commanders are former suppliers (while in the case of Armenians, they are professional soldiers, having fought in Azerbaijan), and so on…

From now until Apr. 8 the films will be shown and discussed in Gyumri, Vanadzor, Noyemberyan and Chambarak.

Epress.am News from Armenia

Epress.am News from Armenia