The geographical center of the South Caucasus, the Azeri village Tekali in Georgia, on this occasion presented itself to human rights defenders, journalists and politicians awash in greenery, dust and partially paved roads.

On Jul. 18, getting off the first minibus to Tekali were civil society representatives from the Armenian town of Noyemberyan and journalists from Yerevan. The buses from Tbilisi, Marneuli and Baku were late: people wanted to see the mined intersection of the borders of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. The last time such an event took place in this village was in March this year.

People were waiting for the guests in the gathering hall of a building named Borchali. Inside was the sharp smell of mutton, being barbecued to be served to the guests after the event.

Helping the owner of the venue were a few young men who had come in their Opels and Volswagens. They understood Russian but preferred not to speak, while the owner happily conversed with the guests. He said that during the Soviet years his family had land in the Armenian town of Stepanavan. He also offered his version of Borchali (also spelled Borçalı, the present-day Kvemo-Kartli region in Georgia mainly populated by Azeris) — a historic area, he said, which extended from Kazakhstan to Stepanavan. The 50-year-old villager’s historical and geographical speculations were interrupted by the tomatoes and eggplants, their hiss indicating that it was time to turn them over on the grill.

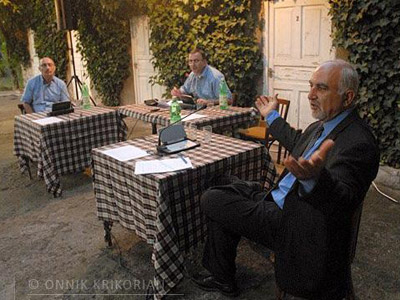

For the second time this year, a mock trial took place in Tekali — this time participants decided to move the tables and chairs outside, under the trees. Union of National Self-Determination (Armenia) party leader Paruyr Hayrikyan and Social Democratic Party (Azerbaijan) leader Zardusht Alizadeh participated in the trial — the former arguing against existing democratic systems and the latter (i.e. the defendant) arguing for.

The key players in the trial arrived an hour and half late. It turns out that Hayrikyan and Alizadeh have many similarities: both have facial hair (Hayrikyan sports a goatee, while Alizadeh sports a mustache); both at one time published a newspaper with the same name, “Independence” (Hayrikyan’s was called “Ankakhutyun” while Alizadeh’s was called “Istiqlal”); and both are bald.

The first to present his argument was Hayrikyan (i.e. the “plaintiff,” pictured below).

Photo by Onnik Krikorian.

Paruyr Hayrikyan, arguing against democratic systems:

“Few consider democracy an ideal means for managing public life, but nothing better has been proposed yet. Democracy is in crisis. It is one of the challenges, one of the anxieties that has swept the civilized world… The disappointment of the masses is because current democratic systems are not really democratic. Citizens are all equal only on election day — this is the main omission of existing democratic systems. Discrimination begins immediately after tallying up the election results and forming parliament, which lasts until next election day.”

The Armenian politician, drawing formulas, then explained the flawed nature of electoral systems, even in those countries that are considered to be the bulwark of democracy.

Hayrikyan was proposing a system in which no vote will remain outside the process of governance. Losing candidates cannot become MPs, but they can decide to which of the elected deputies they can transfer the votes they received. They can declare this even during the election campaign.

Thus, the ballot becomes a power of attorney which a citizen temporarily entrusts to any political entity or individual so that the latter makes decisions on his or her behalf. If the MP doesn’t justify himself then in the next election he will lose the ability to obtain this “power of attorney” from disappointed voters.

Photo by Onnik Krikorian.

Zardusht Alizadeh (pictured, above), arguing for democratic systems:

“The crisis of democracy is global and includes a wide spectrum from morality to economics. But what prescription is Mr. Hayrikyan offering? The meaning of his proposal is to provide real equality of all citizens not only on election day, but during the entire operation of the elected body.”

According to Alizadeh, to improve the existing systems of democracy, the construction material with which the establishment of democracy is built needs to be improved. It is impossible to build a democratic state without a democratic citizen. If a voter is ignorant, has no assets, is poor and dependent, has no sense of responsibility, the ability to think logically or foresee the consequences of his decisions, then not even the most ideal voting system will be able to strengthen democracy.

“The voting or electoral system itself is not able to change the political culture of imperialist states, for which international law is just a cover for their violent actions aimed at ensuring the benefits and profits of multinational companies. No, even the most perfect system of voting cannot change the logic of state officials of democratic governments, who justify the deaths of civilians during military operations.”

Alizadeh noted that he could speak of Armenian elections and Armenian voters, citing the opinion of Vardan Harutyunyan, “a highly respected man for me,” but he will speak of his own experience instead:

“I have participated in all election campaigns in Azerbaijan since 1989. In my country, all elections without exception have one thing in common: their results were rigged by the executive branch [of the government]. All elections — presidential, parliamentary, municipal, judicial — are rigged. In such a situation, how can one hope to account for the votes of the losers when even the votes of the winners are discarded?”

Photo by Onnik Krikorian.

According to the defendant, the inadequacy of the existing electoral system refers to the systemic and structural defects of democracy itself, which can only be eliminated by eliminating democracy as a system of government. “The ideal is unattainable because it doesn’t exist. It is not in people nor in a community of men. It remains to ascertain that the ideal is in God, the perfection of which people must seek for a lifetime. But, alas…”

Alizadeh immediately dispelled his persuasive pessimism, saying he would vote for Hayrikyan. This was perhaps the decisive factor in the subsequent voting: 26 people voted in favor of the plaintiff (Hayrikyan) and 17 voted against, while the rest abstained.

Photo by Onnik Krikorian.

Was there more democracy and freedom in the South Caucasus after this next peace initiative, a symbolic trial, a meeting of journalists and experts from conflicting (and not so) countries? It’s hard to say. But there was more freedom and transparency in a village in southern Georgia, just north of Armenia and slightly west of Azerbaijan, than in the Marriott Hotels and Sheraton Plazas of Tbilisi, Baku and Yerevan, at an event organized by the Caucasus Center of Peace-Making Initiatives (Armenia), the Tekali Association (Georgia) and the Women’s Alliance for Civil Society (Azerbaijan).

It’s difficult to resolve issues in the South Caucasus overnight to say the least, and the borders won’t open tomorrow, but there is something positive that happens at such gatherings — human rights defenders defend human rights and journalists do not serve the authorities…

Photo by Onnik Krikorian.

Epress.am News from Armenia

Epress.am News from Armenia