Since breaking away from the former Soviet Union 20 years ago, Georgia’s ancient traditions have become more popular than ever — including a more environmentally friendly version of the Christmas tree, reports the BBC‘s Damien McGuinness in Tbilisi.

Gizo Toidze, 75, has been making Georgian-style Christmas trees for more than half a century.

Chichilakis are straight hazelnut branches, shaved into the shape of a small coniferous tree, varying in length from 20cm (8in) to a few metres.

Sitting in front of a wood fire at his home, Toidze first strips the bark off the branch, and then shaves the pole with a sharp knife, leaving the curly fronds attached to the top.

It usually takes him about half an hour to makes an average-sized chichilaki, which he then sells for about a dollar. Last year he made 700.

The village where he has lived all his life, Bagvaneti, is at the foot of the Caucasus Mountains in the western region of Guria — the spiritual homeland of the chichilaki.

But Toidze says he has noticed a marked increase in demand for chichilakis over the last few years across the whole country, particularly in the capital, Tbilisi.

People who fled the separatist wars of nearby Abkhazia in the early 90s brought their rural traditions with them to Tbilisi. And now they seem to have caught on among urban types too.

But Gizo says the chichilaki is also becoming more popular because it is better for the environment than destroying pine trees.

“To make a chichilaki we only use branches which have been pruned from the tree anyway to keep it healthy,” he says, as he chops away at a hazelnut branch. “If you chop down pine trees for Christmas, you kill the forest.”

Emotional attachment

The environment is not often a top priority in Georgia. Poverty levels are high and many people with barely enough money to live on have more pressing concerns.

And mainstream Georgian society has yet to embrace green issues — plastic bags are handed out in shops for even the smallest individual purchase; recycling is virtually non-existent; and the government recently scrapped the ministry of environment, incongruously placing all ecological issues into the hands of the ministry of energy.

But when it comes to trees, it is a different story. Many Georgians feel an emotional, and at times patriotic, attachment to the forest.

And during the 2008 war with Russia, the destruction of woodland not far from the disputed region of South Ossetia provoked national mourning.

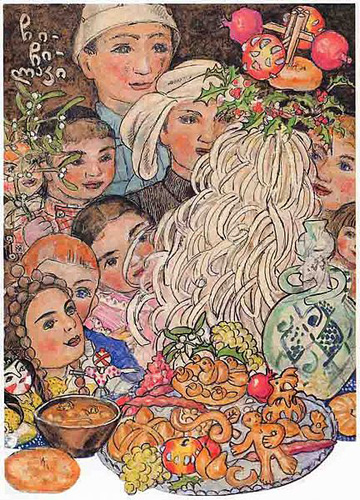

“For me and my family, cutting down a pine tree for Christmas would be a tragedy,” says Tbilisi resident Sophio Phitskhelauri, as she and her two young daughters decorate their chichilaki with fruit and sweets. “We are very much against it.”

“We put up a chichilaki every year. It is our tradition, and because we want to protect the environment.”

With many families opting for a pine tree as well, however, the chichilaki on its own will not necessarily save the forest.

So to stop people chopping down Christmas trees, for the first time the government has now introduced massive fines. Anyone found cutting down or transporting a pine tree without proof that it was grown at a registered farm will be fined up to $1,200, three times the average monthly salary.

And in the run-up to Christmas, forest rangers are now tripling the number of patrols to stop pine trees being felled illegally.

But environmentalists are sceptical that this will help tackle deforestation.

Irakli Matcharashvili, from the Georgian environmental group Green Alternative, says it is simply a public relations exercise to convince voters of the government’s green credentials.

“It looks good for the government if they punish individuals for cutting down Christmas trees,” he says.”But the main problem is commercial logging. Huge amounts of trees are cut down and exported. And there is no monitoring.”

Matcharashvili says the main concern is the unregulated commercial exploitation of Georgia’s forests, not individuals cutting down Christmas trees.

The deforestation is increasing the number of landslides because of Georgia’s mountainous landscape.

Soviet ban

The growing popularity of the chichilaki is part of a wider trend. Georgians have always proudly hung onto their ancient and unique heritage.

But increasingly these traditions are becoming ever more popular right across society — from young fashion designers making hip updated versions of the country’s traditional costume, the chokha, to the massive surge in popularity of the Georgian Orthodox Church among young people.

Under Soviet rule, Moscow allowed Georgia to keep certain aspects of its culture. But the sale of chichilakis was banned.

It was condemned by the Soviets as a religious symbol because the bushy fronds represent the enormous beard of the 4th Century saint, Basil.

Today that has all changed.

In the run-up to the Georgian Orthodox Christmas, which is celebrated on Jan. 7, market stalls in Tbilisi will be packed with elderly craftsmen like Toidze selling their homemade chichilakis.

The chichilakis will then be burnt on Jan. 19, the feast of Epiphany, to symbolize getting rid of the previous year’s worries.

Meanwhile, Toidze has finished making his chichilakis for the day, and for the rest of the evening he will take part in another important national tradition — sitting round a table with his friends knocking back lots of Georgian red wine.

Epress.am News from Armenia

Epress.am News from Armenia